Monthly Growth Scan

Abstract

This article examines other sources that discuss the policy of economic growth, focusing on sources from January, 2011.

January has ushered in 2011 with a revolutionary roar that may help us to understand a key waypoint along the treacherous slopes of growth. The last Democracy Now! broadcast for January was entirely dedicated to the ongoing uprising in Egypt; in it, Amy Goodman interviewed Samer Shehata about the situation in Egypt, who provided a brief history lesson:

[B]eginning in 2004, of course, Egypt began implementing economic reforms called for by the IMF—or really forced on them by the IMF and the World Bank—from the late 1980s and the early '90s, economic reform and structural adjustment programs of privatization, subsidy cuts, opening up markets, deregulation and so on. But the Egyptian government did it in a very hesitant fashion, unwillingly at first. But in 2004, something radical happened, and a new government was appointed, new ministers were appointed, who believed wholeheartedly in the ideas of the IMF and the World Bank. And they quite vigorously pursued these policies. And there was at one level, at the level of macroeconomic indicators, statistics, GDP growth rates, foreign direct investment and so on—Egypt seemed to be a miracle. And this, of course, was the case with the Tunisian model earlier. You'll remember that Jacques Chirac called it the "economic miracle," and it was the darling of the IMF and the World Bank, because it implemented these types of reforms earlier. Well, of course, we saw what happened in Tunisia. In Egypt also, from 2004 until the present, the government and its reforms were applauded in Washington by World Bank, IMF and U.S. officials. GDP growth rates were above six percent in consecutive years. Egypt received the top reformer award from the IMF and the World Bank, tremendous foreign direct investment.

But what all of that masked, what all of that masked, was what was going on at the level of real people and ordinary lives. Real incomes were declining as a result of incredibly high inflation, not as high as in Zimbabwe or Venezuela, but inflation rates of 25, 30 percent, eating away at people’s incomes. Basic commodities, foodstuffs, prices were increasing tremendously. In 2008, about 13 or 14 people, Egyptians, died as a result of conflicts resulting from them waiting in long bread queues, because there wasn’t enough bread, and violence would erupt.

The Oil Drum adds some interesting additional analysis of the situation, from the perspective of energy policy, as you might expect.

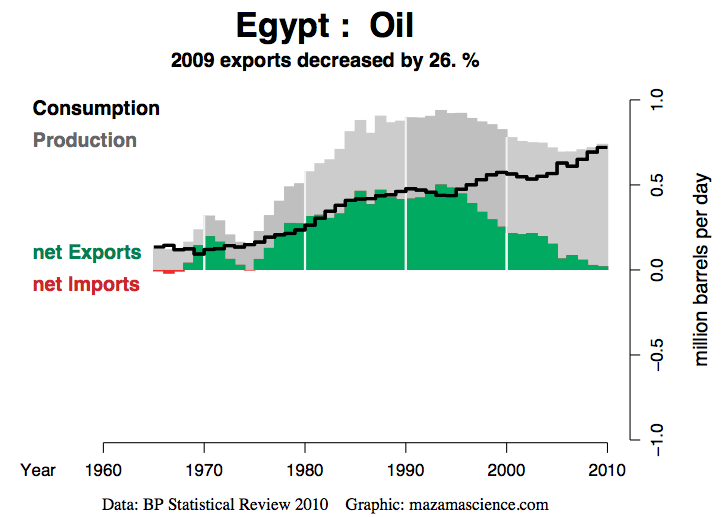

There is a good reason why one might expect Egypt to start running into problems with energy and food subsidies. Its own financial situation is declining at the same time that the cost of food imports is soaring. If we look at a graph of Egyptian oil imports, exports, and consumption ..., we find that Egypt’s oil use has been rising rapidly, at the same time the amount extracted each year is declining.

So where do we see commentators praising economic growth this past month? Not just commentators, but leaders charged with extreme power direct us toward the shimmering goal of prosperity through economic growth. Leading these leaders, President Barack Obama gave prominence to the need for economic growth in his State of the Union address on January 25th. Two days later, the President also answered some citizen-submitted questions in a YouTube interview, in which at one point he emphasized economic growth twice in 20 seconds. In an ongoing display of corporatism that vividly illustrates who really benefits from economic growth, President Obama selected William Daley—who could power a small city with his trips through the revolving door (going from the Amalgamated Bank of Chicago to the board of Fannie Mae to the U.S. Secretary of Commerce to President of SBC Communications to executive at JPMorgan Chase, with a lot of other corporate ties as well)—as his new Chief of Staff. And see what Obama has to say about him:

Few Americans can boast the breadth of experience that Bill brings to this job. He served as a member of President Clinton’s cabinet as commerce secretary. He took on several other important duties over the years on behalf of our country. He’s led major corporations. He possesses a deep understanding of how jobs are created and how to grow our economy. And needless to say, Bill also has a smidgen of awareness of how our system of government and politics works. You might say it is a genetic trait. But most of all, I know Bill to be somebody who cares deeply about this country, believes in its promise, and considers no calling higher and more important than serving the American people.

President Barack Obama on Tuesday ordered a review of U.S. regulations, both old and new, in a push to blunt criticism from Republicans and businesses that excessive government is hindering economic growth.

As we've seen before, the impetus for economic growth remains an unquestioned bipartisan consensus; party differences arise from how best to facilitate that growth. The title of the following article provides a pretty good summary of the conservative position: Key Republican: We can cut budget and grow economy. When Republicans push for freeing up capital locked in entitlement programs, note how the Democratic response still emphasizes growth:

Such across-the-board cuts “would have very damaging implications for the long-term growth of the economy and the long-term future of our work force,” said Jacob J. Lew, Mr. Obama’s budget director.

Obama's popularity was recently measured by Gallup as breaking above 50 percent -- an eight-month high -- and that is at least in part attributable to the recent resurgence of economic growth.

The article The Economy in 2011 asserts that “[t]he question for 2011 is whether growth will ever translate into broad prosperity.” That's a bit strange; is The New York Times questioning our growth policies? Let's dig a big deeper. “[G]rowth is not expected to be strong enough to make a real dent in unemployment, which at 9.8 percent remains close to the recession’s peak of 10.2 percent in October 2009.” Ah, so what you're telling me is that what we really need is a sufficiently large rate of growth. Krugman, can you back us up, here?

Jobs, not G.D.P. numbers, are what matter to American families. And when you start from an unemployment rate of almost 10 percent, the arithmetic of job creation — the amount of growth you need to get back to a tolerable jobs picture — is daunting.

First of all, we have to grow around 2.5 percent a year just to keep up with rising productivity and population, and hence keep unemployment from rising. That’s why the past year and a half was technically a recovery but felt like a recession: G.D.P. was growing, but not fast enough to bring unemployment down.

Yesterday's upbeat new home sales data inspired the private forecasting firm Macro Advisers to double down on their prediction that GDP growth for the first quarter will be a very robust 4 percent. On Friday, the government will release its first stab at estimating fourth quarter growth, and the consensus prediction right now is around 3.7 percent.

The closely watched survey of manufacturing conditions released every month by the Philadelphia Federal Reserve Bank indicated continued industrial growth. ... The numbers don't scream rapid growth. Slow and steady is still the watchword, and there are clear warning signs.

It could become an all too familiar and discouraging narrative for the 21st century -- constraints on the supply of cheap energy act as a capacity regulator that chokes off economic growth every time the business cycle starts hopping. Who knew the Industrial Revolution would ultimately prove to be so ironic?

Many people look at economic growth as an indicator of future prosperity. As 2011 began, it seemed like many analysts looked at the growth of manufacturing with optimism. Reporting on a recent Detroit auto show, one report said that “[m]ost analysts expect double-digit growth in 2011 and further gains in 2012.” Another report cheers that Manufacturing grows, bolsters 2011 outlook. I always chuckle at the morbid irony embedded in blatant contradictions such as the one between the title Factory orders rebound, brighten growth view and this statement from that article:

New orders received by factories unexpectedly rose in November, and orders excluding transportation recorded their largest gain in eight months, providing more signs the economic recovery was on sustainable path.

[h]ouseholds have been borrowing less and saving more since the recession began in December 2007. This has been a major factor holding back overall economic growth because it has dampened consumer spending. Consumers account for 70 percent of total economic activity.

Unsurprisingly, an emphasis on growth exists throughout the world. French President Sarkozy informs us that in order to achieve critical growth, leaders must have the will to act:

French President Nicolas Sarkozy called in a speech laying out his G20 agenda Monday for new rules to curb commodity price volatility, warning that the world risks food riots and weaker growth if leaders fail to act.

The World Bank estimates that global GDP, which expanded by 3.9% in 2010, will slow to 3.3% in 2011, before it reaches 3.6% in 2012. Developing countries are expected to grow 7% in 2010, 6% in 2011 and 6.1% in 2012. They will continue to outstrip growth in high-income countries, which is projected at 2.8% in 2010, 2.4% in 2011 and 2.7% in 2012.

Is anyone trying to steer us away from this insanity? The Nation has started a good video series called Peak Oil and a Changing Climate, and many of the guests in that series discuss the problem of unlimited economic growth. Also, Foreign Policy magazine ran a fun anniversary report called Unconventional Wisdom that included an essay by Thomas Homer-Dixon titled Economies Can't Just Keep On Growing, which presents a radical truth right there in the title. (The picture leading off that article is dramatic.) Here's an excerpt:

We can't live with growth, and we can't live without it. This contradiction is humankind's biggest challenge this century, but as long as conventional wisdom holds that growth can continue forever, it's a challenge we can't possibly address.

See the version of this page with comments enabled to read or add comments.